Comparing Violence Agains Men and Women in Brazil

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

The relationship between the Maria da Penha Police and intimate partner violence in two Brazilian states

International Periodical for Disinterestedness in Wellness volume xv, Commodity number:138 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Globally, inequality between men and women manifests in a multifariousness of ways. In particular, gender inequality increases the risk of perpetration of violence confronting women (VAW), especially intimate partner violence (IPV), by males. The Earth Wellness Organization (WHO) estimates that 35 % of women accept experienced physical, psychological and/or sexual IPV at least once in their lives, making IPV unacceptably common. In 2006, the Maria da Penha Law on Domestic and Family Violence, became the first federal law to regulate VAW and punish perpetrators in Brazil. This study examines the relationship between Brazilian VAW legislation and male person perpetration of VAW by comparing reported prevalence of IPV before and after the enactment of the Maria da Penha Law.

Methods

To assess changes in magnitude of IPV before and after the police force, we used data from the 2013 Brazilian National Health Survey; we replicated the analyses conducted for the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women'southward Health and Domestic Violence Confronting Women-whose data were collected before the passage of the Maria da Penha Constabulary. Nosotros compare findings from the two studies.

Results

Our analyses evidence an increase in the reported prevalence of physical violence, and a decrease in the reported prevalence of sexual and psychological violence. The increase may result from an bodily increase in physical violence, increased awareness and reporting of physical violence, or a combination of both factors. Additionally, our analysis revealed that in the urban setting of São Paulo, physical violence was more probable to be severe and occur in the abode; meanwhile, in the rural state of Pernambuco, physical violence was more likely to be moderate in nature and occur in public.

Conclusion

The Maria da Penha Law increased attention and resource for VAW response and prevention; however, its true impact remains unmeasured. Our information suggest a need for regular, systematic collection of comparable population-based data to accurately estimate the true prevalence of IPV in Brazil. Furthermore, such data may inform policy and program planning to address specific needs beyond various settings including rural and urban communities. If routinely collected over fourth dimension, such data can be used to develop policies and programs that address all forms of IPV, too as bear witness-based programs that address the social and cultural norms that support other forms of VAW and gender inequality.

Background

Globally, inequality between men and women manifests in a diverseness of means. In particular, gender inequality increases the risk of male perpetration of violence confronting women (VAW), especially intimate partner violence (IPV), among other hazard factors [1–3]. Violence and the fearfulness of violence significantly touch women's health and well-being. The broad-ranging health consequences of VAW include: physical injury, chronic hurting, gynecological disorders, unintended pregnancy, low, alcohol and substance abuse, mail-traumatic stress disorder, suicide, and death from femicide [4–vi]. Moreover, these health consequences are cumulative [seven].

Predictably, women with experiences of IPV report higher rates of health bug when compared with women who have never experienced such violence [4–6]. Equally a result, women who take experienced IPV bear a disproportionate burden of injury, affliction, disability, and death, suggesting that widespread male perpetration of VAW is non merely a stark manifestation of gender inequality, just also a significant contributor to health inequalities [5].

The fact that VAW is a global phenomenon underscores the pressing demand for prevention and intervention strategies. The Earth Health Arrangement (WHO) estimates that 35 % of women have experienced either physical, psychological and/or sexual intimate partner violence or not-partner sexual violence in their lifetime [half dozen, 8]. This makes the occurrence of IPV unacceptably common [5].

Schraiber et al. performed a land-level assay of Brazil-specific information from the 2003 WHO Multi-Land Report on Women's Health and Domestic Violence (WHO MCS-Brazil). The study yielded estimates of reported lifetime prevalence of IPV among women in the urban center of São Paulo and in Zona da Mata, a rural region in the northeastern land of Pernambuco [nine]. The analysis revealed disparities in IPV victimization betwixt urban and rural settings, with the latter presenting higher estimates beyond all types of violence. Psychological violence (41.8 % and 48.nine %), concrete violence (27.2 % and 33.vii %), and sexual violence (ten.1 % and xiv.3 %) were reported in the urban and rural sites respectively [ix]. These differences may be evidence of the urban-rural gap, regional differences, or both. Given the underreporting of violence, these estimates are peculiarly alarming [five, nine].

Increasing global recognition of VAW every bit both widespread and preventable has given ascent to diverse prevention and intervention strategies. The United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Bigotry confronting Women (CEDAW), the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women (Convention of Belém do Pará), and similar international guidelines support this recognition and encourage national-level adoption of legislation and policy that promotes gender equality and addresses VAW [ii, x, 11].

In Brazil, the national legal and regulatory structures for promoting gender equality and addressing VAW began with the signing of CEDAW in 1984 and the constitutional recognition of gender equality in 1988 [2, 11]. In the final 15 years Brazil has significantly expanded its national response to VAW, largely due to international and domestic pressure, specially by the Brazilian women'southward movement [2, 11, 12]. In 2002, CEDAW received national approval, nearly eighteen years later on its initial adoption by the Brazilian government. Shortly thereafter, in 2006, Law No. xi.340, the Maria da Penha Law on Domestic and Family Violence, became the beginning federal police to regulate VAW and punish perpetrators in Brazil [2, 11, thirteen, xiv]. The Maria da Penha Police force defined forms of domestic and family violence and created mechanisms to reduce and prevent VAW. These methods include preventive detention for individuals deemed at risk for violence perpetration [2, 13, 14].

Though legislation and policy are critical to VAW response, the prioritization of criminal justice interventions, which include castigating measures for perpetrators (east.g., criminal sentences) and protective measures for survivors (e.chiliad., restraining orders), have come under increasing scrutiny [12]. These types of interventions tin can lead to unintended consequences that result in harm to the women they are intended to help [7, 10]. In fact, international research shows that unenforced and partially enforced VAW laws can really facilitate the male perpetration of IPV [ane, 5, 7, xi].

A 2013 survey conducted by the Patrícia Galvão Plant and Data Pop Institute on societal perceptions of VAW in Brazil revealed the perceived impacts of the Maria da Penha Law [15]. The report found that nearly all Brazilians (98 %) had heard of the law, and the majority were familiar with its purpose and function (66 %). Most (86 %) believed that more than women have reported cases of domestic violence following the law, and many (85 %) agreed that women who study violence risk further harm in doing so. Well-nigh participants (88 %) reported that gender-based homicides against women, known as femicides, had increased in the terminal 5 years. These survey findings suggest not only that the Brazilian public is knowledgeable almost VAW legislation, but also that women actively utilize its mechanisms to denounce violence. These are reassuring findings considering that VAW legislation is intended to provide recourse for women who feel or are at risk of violence. However, these findings also advise that the Brazilian public perceives that women put themselves at an increased risk for violence by using these mechanisms, and that femicide has increased in the years following the passage of the Maria da Penha Law. These findings call for farther exploration into the true impacts of VAW legislation in Brazil.

The purpose of this report is to examine the relationship between the Maria da Penha Law, and the male perpetration of VAW past comparing reported prevalence of IPV before and after the enactment of the law.

Methods

Using data from the 2013 Brazilian National Wellness Survey (Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde; PNS) we replicated the analysis conducted for the WHO MCS-Brazil to examine the human relationship betwixt enactment of the Maria da Penha Law and current IPV prevalence in Brazil [ix, 16]. The results from the WHO MCS-Brazil-conducted prior to the passage of the Maria da Penha Law-was the baseline measure in our analysis. We compare the findings from the WHO MCS-Brazil with our results from the PNS data to assess changes in IPV magnitude after implementation of the Maria da Penha Law.

Design

The first data prepare in our assay was from the WHO Multi-Country Written report on Women's Health and Domestic Violence (WHO MCS). Conducted in ten countries betwixt 2000 and 2003, the WHO MCS was a population-based survey of women aged 15–49 years. Study sites in each country included a uppercase or big city; in some cases a 2d site was based in a province or region. The study's goal was to explore the magnitude and characteristics of unlike forms of VAW, with particular involvement in violence perpetrated past male intimate partners, or IPV. 1 woman per household participated in the study. The WHO MCS-Brazil analyzed the Brazil-specific data [9]. For Brazil, the ii selected sites were metropolitan São Paulo and the rural Zona da Mata region in the state of Pernambuco. Methodological details and ethics approval can exist plant in published written report reports [ix, 17, 18].

The second data source in our analysis was the PNS, alike to the Demographic and Wellness Surveys (DHS). As a collaborative attempt between the Brazilian Ministry of Wellness and the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Establish of Geography and Informatics; IBGE), PNS is a census-style population-based survey. The PNS provides estimates of self-reported wellness, affliction, take a chance factors, and satisfaction with health services. One individual per household–typically the head of household–participated in the study. Methodological details and ethics approval for the original survey tin can be plant in published study reports [16, xix].

The survey information, questionnaires, and codebooks (all in Portuguese) are publicly bachelor [20]. PNS data from the IBGE were cleaned and analyzed with SAS version 9.4 and OpenEpi [21]. Nosotros used the 11 questions pertaining to violence experienced by a known person in order to behave IPV-related analyses. Many questions from the PNS violence module were adapted from the WHO MCS survey instrument assuasive for direct comparing between variables in these two cantankerous-sectional studies.

Data quality check

After merging and cleaning the raw PNS information obtained from the IBGE, we conducted a data quality cheque past replicating the data analysis conducted for the 2013 PNS summary findings [16]. We used Microsoft Excel to randomly select five questions from the PNS for comparison. This was necessary since the code to merge the demographic and violence modules was not included in the downloadable dataset. The results of the quality check resulted in a deviation of no more than i.iv % from the original PNS survey results (0–i.4 %). We determined the acceptable margin of error based on our population and sample size calculations; since our results were within the calculated margin of fault, we deemed a variance of upward to 1.four % acceptable.

Analysis strategy

Using publicly available population-based data our analysis focused on exploring the extent to which the prevalence of IPV increased or decreased later the 2006 Maria da Penha Police force. The comparison of WHO MCS-Brazil and PNS data immune us to examine pre- and post-law data to assess the human relationship between the law and women's experiences of IPV victimization. Restriction variables, namely location, sexual practice, and intimate partner violence, were kept constant.

For the purpose of this study, PNS data were restricted to the states of São Paulo and Pernambuco, modeling later the data nerveless in the WHO MCS. To improve comparability in the final data assay, we used the same methods as the WHO MCS-Brazil for variable categorization. We delimited the PNS dataset to include just female respondents in our assay, thus mirroring the women-only sampling technique utilized in the WHO MCS [18].

Age was grouped into five categories, adhering to the same historic period ranges used in the WHO MCS-Brazil. Marital condition was combined into four categories: currently married, living with partner, separated/divorced/widowed, and single. Frequency of violence was categorized into three categories: one time or twice, iii–11 times, and in one case a month or more than. Severity of violence was determined using the WHO MCS-Brazil definition. Moderate violence was adamant to be exact abuse or "other," based on the available options in the PNS questionnaire; astringent violence included punches, slaps, shoves, threats with a weapon (i.e., gun, knife, or other), choking, burning, and poisoning. Location of violence was complanate into two categories: home or in public. Descriptive statistics were computed and reported in frequencies and percentages. Additionally, nosotros conducted a demographics comparison on the following variables: age groups, marital status, and number of children built-in alive. At that place were no significant demographic differences between the two datasets.

As our overall aim was to place increases or decreases in IPV after passage of the Maria da Penha Police force, we focus on overall prevalence for the time period. Prevalence was estimated by the type of violence reported, and each prevalence was calculated using the number of women experiencing a specific type of violence (i.eastward., physical, sexual, psychological). The denominator was calculated using the total number of women in the ii study sites who had experienced any form of IPV within the previous 12 months. Estimates are presented in proportions (%), with their respective conviction intervals (95 % CI), and were calculated using OpenEpi [21]. We conducted bivariate analyses to compare pre- and post-law prevalence estimates using chi-square tests (or Fisher'due south exact tests, where advisable) for each tabular array. Significance was assessed at α = 0.05 level.

Approval to acquit the original survey is in the respective summary documents [16, 18]. As the dataset used for this secondary analysis did non run across criteria for Title 45 of the Lawmaking of Federal Regulations Section 46.102(f) (2) for human subjects research, the researchers determined that submission to the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB) was not necessary.

Limitations

Despite the comparability between the population-based WHO MCS-Brazil and PNS surveys, at that place are notable differences between the two datasets. The WHO MCS-Brazil was specifically focused on measuring VAW by intimate partners; the PNS was a general survey that included a module on violence. The departure in survey blueprint (i.e., VAW-specific data versus general population), combined with the timing of data collection (i.eastward., earlier and after the Maria da Penha Law) suggests confounding; therefore, our results may not be considered a causal analysis. Nosotros focus instead on characterizing reported IPV before and after implementation of the Maria da Penha Law using the express data available.

Other differences in the datasets including historic period and location sampling are worth noting. The WHO MCS included women anile 15 and over a besides every bit a question about whether or non a woman was ever partnered. The PNS included individuals aged xviii and upwardly and a question about marital status. We causeless that at 18 years of age all women included in the PNS had been involved with an intimate partner at least once. Additionally, the WHO MCS focused on cities and rural areas in Brazil, and had a much larger sample size than the PNS after brake. Despite our modest sample size, we are confident that our statewide data remain comparable because the WHO MCS-Brazil study sites were representative. Additionally, the use of prevalence calculations for the PNS data means that the small sample size did not affect the results of the analysis. Nevertheless, the small sample size does limit the overall generalizability of these results.

Results

Demographics

Amongst PNS participants (North = 2,924), 66.3 % were residents of the state of São Paulo (N = 1,940), while 33.7 % were residents of Pernambuco (N = 984). Overall, the study population consisted of individuals anile eighteen to 49 years. The bulk of individuals were currently married (41.0 %) or living with a partner (xviii.0 %), while 10 % were separated, divorced, or widowed, and approximately 31 % were single. In the 12 months prior to the study, most individuals did non report experiencing any type of violence past a known person (96.5 %, Due north = 2,705); approximately 3.5 % of participants said they had experienced some sort of violence inside this criteria (N = 97) (Tabular array one).

Statistically pregnant differences beyond states existed with regard to marital status, and violence experienced in the terminal 12 months (p < 0.05). The age distribution of female participants in the study was not statistically significant between states (p > 0.05) (Tabular array 1).

Intimate partner violence

Among the women participating in the study and residing in São Paulo or Pernambuco, 43 reported having experienced IPV in the 12 months prior to interview (N = 26 and N = 17, respectively). The well-nigh mutual types of violence were physical (53.5 %) and psychological (39.5 %). No women reported experiencing sexual IPV in the prior 12 months. The severity of violence was approximately even with 44.2 % experiencing moderate violence and 55.eight % experiencing severe violence. However, in São Paulo, severe violence was more commonly reported (61.5 % versus 38.5 %), while in Pernambuco, moderate violence was more than commonly reported (52.9 % versus 47.i %).

The bulk of women who reported experiencing violence, reported these experiences occurring frequently–between three and eleven times over the terminal 12 months (44.2 %); the same was true when information were stratified by land. Overall, violence occurred more frequently at home than in public (São Paulo: 96.2 %; Pernambuco: 76.ii %). Approximately 39.5 % of participants who reported experiencing violence in the previous 12 months reported injury; however, the bulk of these participants (76.7 %) reported that they did not seek out medical attention later on the violence occurred (Table 2).

While differences in blazon, severity, frequency and location of IPV was observed, these differences were not statistically significant when comparing the two states (p > 0.05) (Tabular array 2).

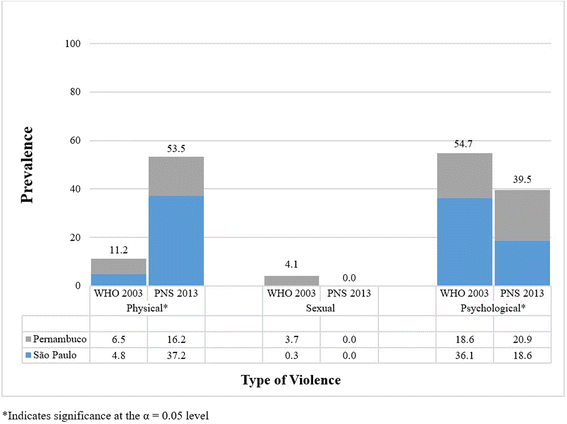

Prevalence of intimate partner violence

Among women who had experienced violence within the 12 months preceding the interview, at that place was a statistically meaning deviation in the prevalence of self-reported concrete violence by an intimate partner before and after the enactment of the Maria da Penha Law. In the WHO MCS-Brazil approximately eleven % (95 % CI: 7.nine, 15.4) of women reported experiencing such violence; by the time of the 2013 PNS, this figure increased to 53.5 % (95 % CI: 37.seven, 68.8) (p < 0.001). The prevalence of sexual violence decreased from 4.1 % (95 % CI: 2.ane, 7.0) to 0 (95 % CI: 0.0, 8.two %) in 2013, and psychological violence besides decreased from 84.7 % (95 % CI: fourscore.i, 88.6) to 39.v % (95 % CI: 25.0, 55.vi). There is a notable deviation in prevalence amongst all types of violence; nevertheless, the decreases in prevalence for sexual and psychological violence were non statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1).

Reported prevalence (%) of intimate partner violence in São Paulo and Pernambuco, among women aged fifteen–49 who have experienced violence within the 12 months preceding the interview–WHO MCS-Brazil (2003; North = 294) and Brazilian National Health Survey (2013; Due north = 43) [ix, 16]

Discussion

In Brazil–a land known for its culture of violence–widespread VAW serves equally a reminder of persistent gender inequality. The 2006 passage of the Maria da Penha Law marked a pivotal moment for the legal protection of Brazilian women from violence. The law has successfully expanded resource to support women who have experienced violence or are at risk of violence, including help centers, shelters, and women'southward police force stations [11]. Still, the true impacts of the law on VAW remains unclear. Every bit an initial examination of this relationship, our study compares IPV prevalence rates using information from the 2003 WHO MCS-Brazil relative to the 2013 PNS data collected following the passage of the 2006 Maria da Penha Constabulary.

Our assay of the PNS information revealed that 2.eight % of participants in São Paulo and 4.7 % of participants in Pernambuco reported experiencing some form of IPV in the 12 months prior to the study. By contrast, the WHO MCS-Brazil reported that 46.four % of participants in São Paulo and 54.2 % of participants in Pernambuco experienced at least one form of IPV. A survey outcome based on the difference in sampling methodologies across the ii studies is the likely explanation for the discrepancy in reported IPV. Full general population-based surveys, such as the PNS, show lower reporting of violence equally compared to VAW-specific surveys like the WHO MCS [22]. Additionally, the methodological differences between the WHO MCS-Brazil and the PNS, every bit well equally a limited sample size based on gender, contribute to this discrepancy.

The WHO MCS-Brazil collected data from each household with a female member, while the PNS used a census-style methodology targeted at gathering data from the head of household. To compare results across studies, we needed to exclude the male person participants based on sex. Our exclusion of male person respondents means that our PNS sample includes just female heads of household or women who responded because the male head of household was absent; some households where IPV was present may take been excluded from our analysis for this reason. Female heads of household may exist less likely to experience IPV, presuming that a male perpetrator is not present in the home. Without specialized grooming on violence amid PNS interviewers, women who responded in the absence of a male caput of household may have felt uncomfortable reporting violence. An underreporting of overall violence past females may have resulted if participants were unsure of whether the male head of household would be informed. Additionally, female respondents who have experienced violence may have refused to answer specific questions or opt out of the PNS entirely. In contrast, the WHO MCS-Brazil included a women-merely sampling method; this was done to avoid putting participants at risk of future violence because of the study and interviewers were trained to disguise the subject matter [18].

Our demographic assay revealed persistent disparities in IPV across urban and rural settings consistent with the findings of the WHO MCS-Brazil. Women in rural settings remain significantly more likely to experience violence than women in urban settings. These data suggest that the enactment of the Maria da Penha Law has washed picayune to narrow the urban-rural gap in IPV prevalence rates. Further inquiry is needed to assess differences in implementation of the law across settings that may contribute to this gap. Our findings may exist evidence of inconsistent application of the law in both settings, including dedicated financial and man resources. The consistent finding of higher levels of IPV in rural settings may justify special attending towards addressing IPV in rural communities. Future IPV prevention and response efforts should advisedly consider any characteristics of rural settings that may contribute to college prevalence of IPV against women.

Moreover, violence prevention strategies and interventions must exist tailored to the realities in a given context, including frequency, location, and types of violence. For example, violence in the urban setting of São Paulo was more probable to be severe in nature and occur in the home, while violence in the rural state of Pernambuco was more likely to be moderate in nature and occur in public. Our findings suggest the normalization or social acceptability of IPV against women varies beyond rural and urban settings. Although IPV may exist less socially acceptable in urban settings, it does occur in more astringent forms in individual spaces. On the other hand, in rural settings, the occurrence of more than moderate violence in public spaces may indicate greater social acceptability of IPV against women in rural settings.

Equally such, strategies and interventions targeting rural and urban settings should address the enabling environs for IPV (e.g., social and cultural norms), equally well as its specific manifestation (e.thou., location, blazon, intensity, frequency). Even though location of violence ("in the home" vs. "in public") was not statistically significant (p = 0.0707), information technology is possible that in that location is a significant difference. Fishers Exact Test was used to compute this p-value due to cell values less than five; therefore, we doubtable this departure may not have exhibited a significant difference due to pocket-sized sample size. While no level of violence is acceptable, public health strategies and interventions must accost social and cultural norms and practices as they exist in the community.

Over time, pregnant increases in reported physical violence and decreases in sexual and psychological violence were observed. In the decade between the WHO MCS-Brazil and the PNS, reported prevalence of physical violence increased (42.three %), a statistically significant finding. There are several explanations for the five-fold increase in reported prevalence of concrete violence during the 10-year menstruation.

One possible explanation is that the increase in reported concrete violence reflects an actual increase in violence. This explanation may reflect a disturbing unintended consequence of the Maria da Penha Law similar to those seen elsewhere in Latin America [7]. Furthermore, for the past decade, Brazil has experienced vast economic growth; millions of individuals rose above the poverty line and income disparity decreased betwixt socioeconomic groups. Studies have shown that there is a full general correlation between violence levels and other crimes; despite the reduction in extreme poverty, which is unremarkably accompanied past a decrease in vehement crimes like homicide, Brazil has witnessed an increase in such crimes over the concluding decade [23, 24]. Therefore, this increment in reported physical IPV could reflect a true increase in physical violence, indicative of deeper issues, including rising homicide levels. Similarly, other inquiry on violence post-obit federal legislation has noted reported increases in VAW, including femicide [7]. More research is needed to assess the ways in which VAW legislation may positively or negatively relate to the male person perpetration of VAW.

A 2nd possible explanation is that the increment in reported physical violence is due to increased awareness and reporting of violence. This explanation reflects an increase in social awareness of VAW at all levels of guild, following implementation of legislation like the Maria da Penha Law. The law was intended as a means of empowering women to denounce violence and seek out justice using legal ways. Additionally, the Brazilian government contributed to increased social awareness past widely disseminating information almost the law, including its purpose, function, and mechanisms. In 2013, but 2 % of the Brazilian population had never heard of the Maria da Penha Constabulary, underscoring the latitude of the regime's far-reaching public awareness campaign [15]. As more and more than women report violence, especially echo violence, in that location will be a natural increase in overall reported prevalence of IPV. Under this view, the increase in reported physical violence since the enactment of the law reflects an increase in awareness, and in office, may address the underreporting limitation acknowledged in the WHO MCS [16]. This limitation may have been lessened farther by increased inquiry on IPV that in and of itself may raise customs awareness.

Finally, one must consider that the increase in reported physical violence could be the combined outcome of increased reporting and increased incidence of violence. If this is the case, the prevalence of IPV will continue to rise over time unless there is an intervention to address the incidence of violence at the customs level in conjunction with improvements in the enforcement of the Maria da Penha Law.

Since the WHO MCS-Brazil, sexual violence decreased by approximately 4 %, and psychological violence decreased by approximately 45 %. The decrease in reported sexual violence is express past a relatively small sample size in our study. All the same, the decrease in sexual violence may be attributable to the Maria da Penha Constabulary, which provides for the criminalization of sexual violence committed past intimate partners. Still, the subtract in reported psychological violence is surprising based on the findings of the WHO MCS-Brazil. According to Schraiber et al., in 90 % of cases, psychological violence is accompanied past physical violence; therefore, we would expect to see trends in psychological violence shadowing those of physical violence [nine]. The Maria da Penha Law defines but does not address psychological violence; this fact that may explicate our finding of a decrease in reported psychological violence. Therefore, policymakers should consider addressing psychological violence straight in the Maria da Penha Law or creating new legislation to address psychological IPV.

Since the enactment of the Maria da Penha Law in 2006, the Brazilian government has actively sought to change societal perceptions of VAW. It has fabricated efforts to more finer enforce the constabulary also as allocate resources to back up those who feel violence or are at gamble of violence. Still the collection and analysis of population-based data regarding VAW and IPV accept been limited. Prior to inclusion of the violence module in the PNS dataset, a comparison similar to the i presented in this article was non possible. While our data provide preliminary insights into changes in violence rates over time, persistent challenges remain in information drove and assay due to a lack of acceptable population-level data. Despite originating from different sources, many aspects of the WHO and PNS datasets were comparable for calculating frequencies and prevalence rates of women'south IPV victimization in Brazil.

To more accurately examine IPV prevalence increases and decreases, nosotros recommend that full general population-based data, including the PNS violence module, is collected routinely for monitoring purposes. In addition, population-based surveys specifically focused on VAW should be administered intermittently to complement these data and account for the previously mentioned survey outcome. In the future, the impact of VAW legislation may be measured through pre- and post-police force data collection using either general or violence - specific, population-based surveys. Additionally, straight cross-sectional comparisons may exist possible, bold that data are routinely nerveless. Qualitative research to place individual and community experiences of IPV and perceptions of related laws would provide additional context.

Conclusion

The Brazilian state has made laudable efforts on the policy front by enacting the Maria da Penha Law in 2006. Since the law went into event, there has been increased attending and resources for VAW response and prevention in Brazil; however, its truthful impact remains unmeasured. Recently, Brazil enacted a Femicide Law that defines the gender-related killing of women and stiffens penalties for perpetrators, including criminal sentences up to 30 years [25–27]. This new law responds to the reality that most murders of Brazilian women are committed by electric current or former intimate partners [13, 27]. The new law is not enough, despite its ground on the United nations Women Latin American Model on Femicide [28, 29].

Our data suggest a need for regular, systematic drove of comparable population-based information to accurately gauge the true prevalence of VAW in Brazil. Policies and programs that address all forms of IPV, as well equally evidence-based programs that accost gender inequality and the social and cultural norms that support them tin can exist developed from these data. The impact of legislation, including the Maria da Penha and the Femicide Laws, can also be evaluated through routine data collection. Such data can inform policy and program planning at all levels in gild to accost specific needs beyond diverse settings.

This written report provides additional bear witness that demonstrates the mixed effectiveness of legislation in preventing or reducing male perpetration of VAW in the Brazilian context. In lite of our findings and the 2015 Femicide Law, the PNS study model should be expanded and adapted to more closely match that of the WHO MCS survey musical instrument. Additionally, a more than exhaustive comparison betwixt pre- and mail-Maria da Penha Law data should be conducted in gild to determine necessary improvements or adjustments to its implementation. Likewise, cross-sectional data should be collected following the Femicide Law to further assess its impacts in conjunction with as well as beyond the Maria da Penha Police. Specific questions regarding individual perceptions and understanding of the Maria da Penha and Femicide Laws would serve to inform future policy and program planning and implementation. IPV disproportionately affects the health and well-being of Brazilian women. To address the enabling social environs, additional policies and programs to ensure more than comprehensive VAW prevention and response are needed.

Abbreviations

- VAW:

-

Violence confronting women

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WHO MCS:

-

Earth Health Organization Multi-Country Study on Women'due south Wellness and Domestic Violence

- WHO MCS-Brazil:

-

World Health Organization Multi-State Study on Women's Wellness and Domestic Violence Study–Brazil

- CEDAW:

-

United Nations Convention on the Emptying of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

- PNS:

-

Brazilian National Health Survey

- IBGE:

-

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Informatics

References

-

Fleming PJ, McCleary-Sills J, Morton Yard, Levtov R, Heilman B, Barker Chiliad. Risk factors for men's lifetime perpetration of concrete violence against intimate partners: results from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) in 8 countries. PLoS Ane. 2015. doi:x.1371/periodical.pone.0118639.

-

Kiss L, d'Oliveira AF, Zimmerman C, Heise L, Schraiber LB, Watts C. Brazilian policy responses to violence against women: government strategy and assist-seeking behaviors. Health Human Rights. 2012;14(1):64–77.

-

Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. Lancet. 2012;359:1423–9.

-

Campbell JC. Wellness consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–6.

-

Heise LL, Raikes A, Watts CH, Zwi AB. Violence confronting women: a neglected public health issue in less developed countries. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(9):1165–79.

-

World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence confronting women: prevalence and wellness effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. WHO; 2013. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/. Accessed 19 Mar 2016

-

Luffy SM, Evans DP, Rochat RW. "Information technology Is Amend If I Kill Her": Perceptions and Opinions of Violence Confronting Women and Femicide in Ocotal, Nicaragua, After Law 779. Violence Gender. 2015;2:107–11.

-

Devries KM, Mak JYT, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, Lim S, Bacchus LJ, Engell RE, Rosenfeld L, Pallitto C, Vos T, Abrahams Northward, Watts CH. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340:1527–eight.

-

Schraiber LB, d'Oliveira AF, França-Junior I, Diniz South, Portella AP, Ludermir AB, Valença O, Couto MT. Prevalence of intimate partner violence confronting women in regions of Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41(5):797–807.

-

Tapia Southward. Violence confronting women, criminalisation, and women's access to Justice in Ecuador and Latin America. In: Lalor One thousand, Mills E, Sánchez García A, Haste P, editors. Gender, sexuality, and social justice: what'due south law got to exercise with information technology? Brighton: Establish of Evolution Studies; 2016. p. 50–7.

-

Roure JG. Domestic violence in Brazil: Examining obstacles and approaches to promote legislative reform. Colum Hum Rts 50 Rev. 2009;41:67–97.

-

Borges CMR, Lucchesi GB. Machismo in the dock: a critical feminist analysis of Brazilian criminal policy apropos the combat of violence against women. Revista da Faculdade de Direito. 2015;sixty(3):249–77.

-

Waiselfisz JJ. Mapa da violência 2012 atualização: homicídio de mulheres no Brasil. FLACSO. 2012. http://www.mapadaviolencia.org.br/pdf2012/MapaViolencia2012_atual_mulheres.pdf. Accessed xix March 2016.

-

Presidência da República: Lei No. eleven.340, de vii de agosto de 2006, D.O.U de 08.08.2006. http://world wide web.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2004-2006/2006/Lei/L11340.htm (2006). Accessed 20 Mar 2016

-

Instituto Patrícia Galvão. Percepção da sociedade sobre violência e assassinators de mulheres. Information Pop; 2013. http://agenciapatriciagalvao.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/livro_pesquisa_violencia.pdf. Accessed 20 Mar 2016

-

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia due east Estatística. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2013: percepção practise estado de saúde, estilos de vida e doenças crônicas. 2014. ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/PNS/2013/pns2013.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2016

-

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg K, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country report on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–9.

-

Globe Health Organization. WHO multi-country study on women's wellness and domestic violence against women: summary written report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. 2005. http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/summary_report/summary_report_English2.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2016

-

de Souza-Junior PR B, de Freitas MP South, Antonaci GA, Szwarcwald CL. Sampling Design for the National Health Survey, Brazil 2013. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2015;24:1–10.

-

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística: Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde: Dados. http://www.ibge.gov.br/domicile/estatistica/populacao/pns/2013/default.shtm (2013) Accessed 15 Jan 2016

-

Dean A, Sullivan Thousand, Soe M. OpenEpi: Open up Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version. http://openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm (2015). Accessed 22 Mar 2016

-

Yount KM, Zureick-Brown S, Salem R. Intimate Partner Violence and Women's Economic and Non-Economic Activities in Minya, Egypt. Demography. 2014;51(3):1069–99. doi:ten.1007/s13524-014-0285-x.

-

Murray J, Cerqueira DRC, Kahn T. Criminal offense and violence in Brazil: Systematic review of time trends, prevalence rates and take chances factors. Beset Violent Behav. 2013;eighteen:471–83.

-

Eisner M. Criminal offense, problem drinking, and drug use: Patterns of problem behavior in cross-national perspective. Ann Am Acad Politico Soc Sci. 2002;580:201–25.

-

BBC News: Brazil femicide law signed by President Rousseff. http://world wide web.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-31810284 (2015). Accessed xiv Mar 2016

-

Presidência da República: Lei No. 13.104, de ix de março de 2015, D.O.U de 13.ten.2015. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2015/Lei/L13104.htm (2015). Accessed 20 Mar 2016

-

Waiselfisz JJ. Mapa da violência 2015: homicídio de mulheres no Brasil. PAHO/WHO, SPM, FLACSO: UN Women; 2015. http://www.mapadaviolencia.org.br/pdf2015/MapaViolencia_2015_mulheres.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2016.

-

United nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (United nations Women). Latin American Model Protocol for the investigation of gender-related killings of women (femicide/feminicide). 2014. http://www.united nations.org/en/women/endviolence/pdf/LatinAmericanProtocolForInvestigationOfFemicide.pdf. Accessed nineteen Mar 2016

-

UN Women. In Brazil, new constabulary on femicide to offer greater protection. 2015. http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2015/three/in-brazil-new-law-on-femicide-to-offer-greater-protection#sthash.D7ZYP4Xx.dpuf. Accessed 23 Mar 2016

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Kathryn Yount, PhD, Robert Bednarczyk, PhD and Samantha Luffy, MPH for their review of the manuscript in accelerate of submission. Additionally, we would like to limited our gratitude to the team responsible for the WHO Multi-Country Written report on Women's Wellness and Domestic Violence for their leadership in addressing violence against women globally and the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia eastward Estatística (IBGE) for allowing open up access to their 2013 PNS data.

Funding

Non applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the IBGE repository, http://www.ibge.gov.br/domicile/estatistica/populacao/pns/2013/default.shtm.

Authors' contributions

MVG was responsible for the acquisition of data, the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revisions. JDW was responsible for the conquering of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revisions. DPE was responsible for the study formulation and design, the acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revisions. All authors read and approved the last manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approving and consent to participate

Methodological details and ethics approval can be found in published study reports [ix, 16–19].

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gattegno, Grand.V., Wilkins, J.D. & Evans, D.P. The relationship between the Maria da Penha Law and intimate partner violence in two Brazilian states. Int J Equity Health 15, 138 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0428-3

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12939-016-0428-3

Keywords

- Violence confronting women

- Intimate partner violence

- Injury

- Injury prevention

- Equality

- Brazil

Source: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-016-0428-3

0 Response to "Comparing Violence Agains Men and Women in Brazil"

Post a Comment